Reblogged bankston:

The Man Is Back

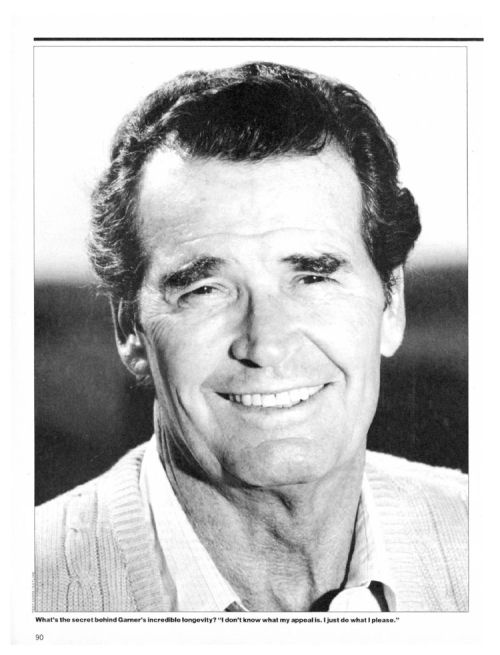

Depression Gone, Hollywood’s Last Real Man, James Garner, Returns to Rugged Form in Space

Look at him. Don’t worry. It’s okay to stare. James Garner is too concentrated on a putt to notice. Dressed in a beige V-neck sweater and slacks, Garner is enjoying his movie star privileges at the Bel Air Country Club. He stands there, without benefit of a filter lens, against a melting sun that would turn even a teen idol like Matt Dillon into a squinting gargoyle, and he looks terrific. Lines, creases and a thickening middle have sculpted character into this open-faced Hollywood hero of the 1960s. At 57, James Garner is wearing exceptionally well. Don’t ask him how he does it. “Looking good doesn’t enter my mind,” he says, grinning that smashing Garner grin.

The modesty, of course, only enhances his appeal. These days Garner is working with a vigor he hasn’t displayed since his time as TV’s Western gambler Bret Maverick and detective Jim Rockford (two dying archetypes he revitalized with humor). In three decades Garner has made nearly 40 films and countless TV shows, but he claims he hasn’t seen more than a third of them. In that, others may wisely follow his lead. Every goody (Victor/Victoria) comes with two clunkers (Mister Buddwing, Tank). Now he’s on a roll—a light-comic actor the experts are starting to take seriously.

This season, with Mary Tyler Moore in Heartsounds, he wowed critics (they’re already talking Emmy) as a doctor struggling with heart disease. “Jim makes it look so easy,” raves Mary. New Oscar winner Sally Field just snagged Garner to play her lover in Murphy’s Romance; she’s smitten. “If men only knew,” sighs Field. “What’s appealing to a woman is how a man makes her feel about herself. Jim is funny and dear, and he laughs at my jokes. That’s what makes Jim sexy; it doesn’t change with years.”

Corroboration of Sally’s statement is available this week as CBS airs Space, a 13-hour, five-night miniseries based on James Michener’s novel. The astronautical epic from Paramount TV cost $35 million, took five months to shoot and boasts 10 big-name stars. Still, the dazzling hardware pales next to Garner, who plays Norman Grant, a World War II naval hero turned senator on a space committee. Playing the hero is nothing new to the stalwart 6’3” actor, but catch his action (he’s hotter than ever) in those love scenes with Blair Brown, playing an astronaut’s wife the married senator takes to bed. “I didn’t want this to happen,” says Brown. “I did,” drawls Garner just before the clinch. That’s it: Just a few words and she’s a goner. Garner’s always been too cool or too shy (deciding which only adds to the fascination) to make the first move. “Every woman wants to be the one who reaches him,” says Brown.

Space is likely to alert audiences to what fans of The Rockford Files have long suspected: James Garner, whose wisecracks can’t hide integrity at the core, may be Hollywood’s last real man. John Wayne is dead. So are Gable, Cooper and Bogart. Who’ve we got now? Eastwood’s tough, but Dirty Harry is rarely good for a laugh. Redford, Newman, Reynolds and Selleck are too wrapped up in movie star vanity to qualify. De Niro, Pacino and Hoffman are chameleons, playing everything from psychos to women. With Garner you know where you stand. The new generation (Penn, Hutton and Cruise) has no history. Garner embodies what critic Tom Shales calls “the crusty, sardonic and self-effacing strain of American masculinity.”

Those qualities are apparent when Garner greets his woman visitor on the golf course. Interviews pain him and he does them rarely. “I hire a PR man just to keep people away from me,” he says. Especially women: “I was a real wallflower as a kid, and women still scare me.” Today he’s brought protection. An avid golfer (he plays the game four times a week when he’s not working), Garner’s lined up two friends and his brother Jack, 59. “That’s what I love about golf,” he says, laying down the challenge. “Nobody can get to you.”

As he settles into the golf cart, his brown eyes flash impishly. “I forgot to tell you, darling,” he says, “I love to race these carts.” It’s mock macho. Throughout the morning he is attentive and chivalrous, offering a gentle hand to my back as we climb a hill and swallowing his profanity when his drive misses the green. Big Jim, who has a six-handicap, is way off his game. “My bad back’[from all those movie stunts] is acting up,” he says. Brother Jack, a golf pro at a nearby club, proves an expert needier. “Now Jim,” he teases, “don’t get that pretty sweater of yours caught in the trees.” Garner grumbles good-naturedly, “It’s a good thing I like to putt.” Does he ever get mad? “Oh, you bet,” says Garner. “It’s a slow process. But when I blow, I don’t care what happens. I once decked a producer at Universal for stealing music and scripts from Rockford. Where I come from [Norman, Okla.], your word is your bond, but I’m in a business where they don’t understand that.” After playing out of a sand trap, he misses an easy putt. Red-faced, he tosses his putter into the air and stands a moment, roiling like an Oklahoma storm cloud. This time the storm passes. “Aw, hell,” he says. “It’s only a game and money.”

At the clubhouse Garner is talking out frustrations, not just his game but his career. “I’m getting too old to play the macho hero,” he says. “I want to play my age.” He’s increasingly terrified of love scenes: “They might laugh at me, and my creed is don’t laugh at me, laugh with me.” Garner liked putting on 15 pounds for Space: “I wanted to be paunchy, a little seedy, that’s what the character calls for.” But don’t think there’s a new De Niro in the making. “I’m a Methodist, but not in acting,” he says, cocking his left eyebrow, the one he uses to show seasoned exasperation. “Little Mariel Hemingway in Star 80,” he says, aghast. “Do you know she had breast implants for the picture?”

Garner will not play a character who strays too far from his personal beliefs. On Space, his first miniseries (at an estimated fee of $1 million), he was a ramrod. “I tried to make the guy less of a wimp than he was in the book,” he says. “I said I didn’t understand how a guy could be a big war hero and then come to the Senate and be pushed around.” Garner also changed the senator from a Republican to a Democrat. “I’m one of those bleeding heart liberals Reagan would like to put behind bars,” he says. “Besides, my wife wouldn’t let me play a Republican.”

Jim is mute about what Lois, his wife of 28 years, thought about his love scenes with Blair Brown, 36. He finds all the sex-symbol talk faintly ridiculous. Brother Jack doesn’t. “It’s not easy being married to Jim,” says Jack, “because of the way fans fall all over him.” Garner laughs it off. Despite an impressive list of screen lovers—including Audrey Hepburn, Natalie Wood and Kim Novak—Garner insists he’s never succumbed to temptation. “Honey,” he says, “I’ve worked with a lot of great-looking actresses, and I make it my business not to dislike any of them. I also make it my business not to fall in love with them either.”

There’s been talk, of course. The Garner marriage has endured two separations, one 15 years ago for three months, another in 1979 that lasted 18 months. During that time he was linked with Lauren Bacall, who had co-starred on Rockford and two films (Health and The Fan). Garner has denied the rumors. “Lois and I were never in serious trouble,” he says, “and everything is fine with us now—99 percent of the problem was the pressures of Rockford. It wasn’t us, it was me needing to get away to get my head together.”

Everything looks serene as we drive up to the iron-gated Garner mansion in Brentwood. The house affords a view from every room, but the world is locked outside. Lois wants none of her husband’s public life. Garner met aspiring actress Lois Clarke at an Adlai Stevenson rally in 1956 (“She just knocked me out”). They were married two weeks later. Lois had a daughter, Kim, by a former marriage. Kim, now a teacher in L.A., came to live with them. Two years later daughter Gigi was born. A country singer, Gigi has settled in Nashville. “I think she sings pretty good,” Garner deadpans. He is never more exasperatingly laconic than when speaking of his family. Lois has helped fill in some of the blanks: “Jim is a rather complicated man and is covering up lots of hurt. Growing up he was abused, lonely and deprived.”

The youngest of Mildred and Weldon Bumgarner’s three sons, he had a childhood that played like a modern day Oliver Twist. He was only 5 when his mother died. The boys—Jim, Jack and Charles (a former high school shop teacher who died last year)—were farmed out to various relatives. Three years later the family was reunited when Weldon (who subsequently married four times) introduced them to their first stepmother, a mean-spirited woman who regularly beat them. “Mostly me,” says Jim. Weldon was no comfort. “My dad worked hard as an upholsterer and carpet layer,” says Jim, “but he was a rake and he drank a lot. He’d come home bombed and make us sing to him or get a whipping.” Garner’s sympathy for the underdog comes from this. “I cannot stand to see little people picked on by big people,” he says. “If a director starts abusing people, I’ll just jump in.”

At 14, he left home and did odd jobs. Two years later he lied about his age and joined the merchant marine, but left in less than a year. He drifted to L.A., where his father then lived with his third wife, and attended Hollywood High. Jim was a football hero, but shy off the field. “All the girls liked him,” says a childhood friend, Bill Saxon, “but Jim hardly dated.” Still his hunky teen torso won him his first on-camera job: a Jantzen swimsuit ad. He grimaces: “Ever since I did that darn ad, I’ve hated having my picture taken.”

The Korean War interrupted his modeling career. He was wounded twice and won two Purple Hearts. On his second day in Korea, he was hit by a shard of shrapnel. Later, he says, “our own jets strafed us. I went for a foxhole, and a South Korean soldier dived on top of me.” Garner spent three months recuperating from a dislocated shoulder and knee injuries. Typically he pooh-poohs accusations of bravery. “I wasn’t a hero,” he says. “I just got in the way a lot.”

It was also luck, he claims, that got him into acting. Paul Gregory, a soda-jerk pal from back home who had become a producer, gave him the small role of a judge in Broadway’s The Caine Mutiny Court Martial. The star of the show, Henry Fonda, became his mode! and mentor: “I learned just watching him act.” Warner Bros, made Garner a $500-a-week contract player in such unremarkable flicks as Toward the Unknown and Darby’s Rangers. Then, in 1957, they gave him Maverick at the same low price. The series made him a star, but not rich. After four years he had to sue his way out of the series.

Money matters had improved dramatically (an estimated $50,000 per episode) at the time Garner signed up for The Rockford Files in 1974. Still, at the end of 1979, Garner quit the series (perhaps the best ever in the detective genre), again in bitterness. He has filed a $22.5 million suit against MCA/Universal, the owners of Rockford, charging that the studio had cheated him out of his share of the profits. “They made $150 million on Rockford and, even though I owned 37.5 percent of it, I’ve yet to see the money.” Many similar cases are settled out of court. Garner, ever the man of principle, intends to go all the way, no matter how long it takes. “I ruined my health with all those stunts and long hours,” he says. “But I figured I was creating an annuity. The crew used to joke, ‘Come on, it’s Garner’s money we’re wasting.’ When I found out there were no profits, it turned me off this business.” He slid into despair. “I was going to chuck everything,” he has said. “The business. The family. Everybody can go to hell.” His poor health didn’t help. In 1980 he announced, “I’m constantly in pain. I have arthritis in my back and my knees and my hands. I had ulcers this year—and once an ulcer patient, always an ulcer patient. I get depressed. Very.” He saw a psychiatrist, split from his family and tried to work it out “before everything was ruined.” That he did work it out is a tribute to Garner. And Lois. “She’s just stuck with me all these years,” he says. “I guess she’s stubborn too.”

Gazing out on his garden, Garner smiles. “I love to sit under the trees and read.” Don’t bet on early retirement. In Heartsounds (“the one I did for love”) Garner played a man facing his own mortality. To act it with dignity, he drew on an inspiration: Henry Fonda. “I knew Henry very well,” he says softly. “I used a lot of his attitudes—his crotchetiness, his wit, his fight against something he couldn’t control.” Garner is unembarrassed by the emotion in his face. The rest he can’t put into words. He doesn’t have to. Fonda was the kind of man who lived by a code of honor. So is James Garner.

The Last Real Man - People Magazine

No comments:

Post a Comment